Untitled

- NJ

- Nov 2, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Dec 9, 2025

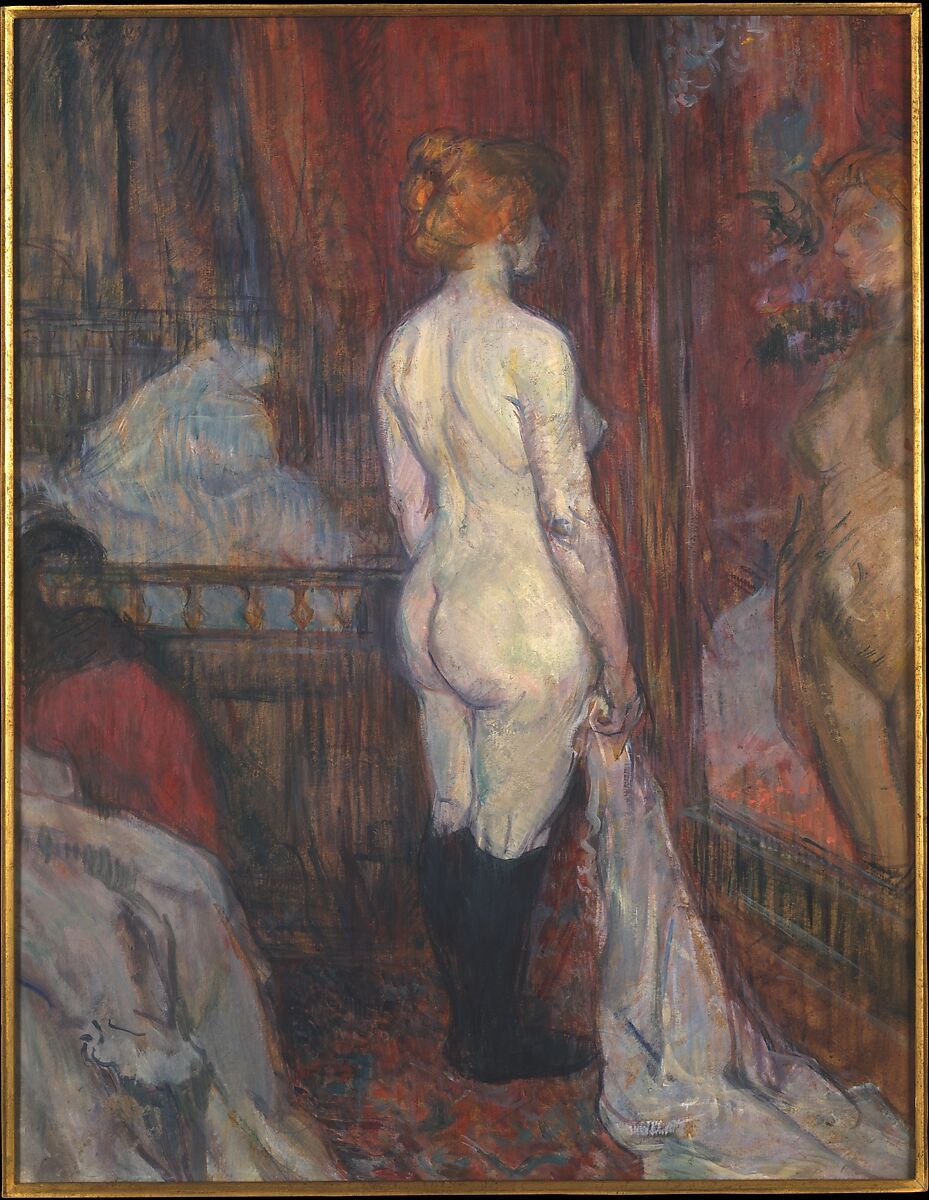

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, “Woman Before a Mirror” (1897)

TW: contains references to sexual trauma, domestic violence and medical trauma. Please read with care.

If you asked me how many men have tried to kill me, I’d probably laugh before I answered.

Then I’d start counting.

I’d have to use my fingers. The same ones I used to count which friends to invite to my princess birthday party when I was six.

(FYI: Stephanie Holland didn’t make the cut.)

In fact, it’s happened so often that I’ve wondered over the years whether they have a point.

What stayed with me most that night wasn’t the suffocating weight of his hands tightening around my throat, lifting me off the floor, as my toes reached for stable ground.

It wasn’t being thrown onto the balcony like a dog, the sliding door slamming shut behind me, his cold words trailing in its wake:“…until you’ve learned your lesson.”

(I’m still not sure if the lesson was anything more sophisticated than: Obey, or die. Mind you, he was about as sophisticated as a Greggs sausage roll in a tuxedo, so I shouldn’t be surprised.)

It wasn’t my blood spreading across the white tiles like a dark omen, or the echo of my own screams bouncing off the walls.

It wasn’t the certainty that I was dying, nor the image of him, sitting on the bed, calmly watching life slip away from me.

It wasn’t the sound of worried strangers or the door breaking, or the kind nurse who held my hand during surgery, maternally stroking my hair as a substitute for the anaesthetic I couldn’t have.

No, what stayed with me most was the radiologist’s face - his smug smile - and his podgy, tanned sun-cracked hands lifting the fabric of my top, casually covering my face as if I were nothing more than a thing to be violated.

Some men don’t just take power.

They delight in watching you realise you never had any in the first place.

The man who went home to his wife the next morning and sat down at their kitchen table with the sun beaming through the window. Watching his daughter revise for her science test, happily eating her eggs on toast, and having her head lovingly stroked by those same podgy fingers.

Decades later, I still wonder where that podgy-fingered man is now.

Is he dead? Probably.

I wonder if his grandchildren wept at his graveside.

Devastated at the loss of a “good man.”

And the most unsettling part?

The total acceptance I felt: that this is just how things are.

The part of me that just added it to the ever-increasing pile of ‘Shit Men Do’.

I try and tell myself that my silence wasn’t consent, it was survival.

But what if it was cowardice?

What if I wasn’t just young and terrified and bleeding, but ‘weak’, too?

What if my silence wasn’t just shock, but some ancient instinct to please, to not make it worse, to be the Good Girl…even while dying?

What if I helped them both - them all - get away with it?

I know what this sounds like.

Like I’m blaming myself.

But I’m not.

I’m tracing the way the world taught me to be quiet.

The way complicity was the cost of survival.

I’ve swallowed that guilt long enough to know: it doesn’t belong to me.

But trauma doesn’t care about fairness.

It loops back in whispers and accusations, in moments when you’re doing the dishes twenty years later, and suddenly you’re back on that cold hospital table with that podgy fingered man.

Trauma rewrites you.

And it keeps asking the same question in a hundred different forms:

Why didn’t you fight harder?

But maybe the better question is:

Why did I have to fight at all?

Why was it always up to me to prove I had a right to breathe?